WFSE Members Ensure Labor Laws Apply to ALL Washingtonians

The detainees at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma are not being held for criminal punishment; they are immigrants and asylum seekers being held until their immigration status is sorted out.

For years GEO Group, the corporation that owns the detention center, has relied on the detainees to keep their facility clean and to keep the detainees fed, paying as little as $1 a day or sometimes just extra food.

A longshot case from the beginning

Despite this arrangement being a clear violation of Washington State’s minimum wage law, the case was a longshot from the moment Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson sued GEO Group in 2017.

For one, jury trials set a very high bar. In federal court, jurors must agree on the verdict unanimously. Never easy, coming to a consensus in this case would prove especially difficult because it involved the politically-charged subject of immigration.

Further stacking the odds against the attorney general’s office? GEO Group, unlike the state of Washington, has near-endless funds from which to draw. Over the course of the trial the corporation would use no fewer than 28 attorneys in its defense.

“The state was the scrappy underdog in this case.”

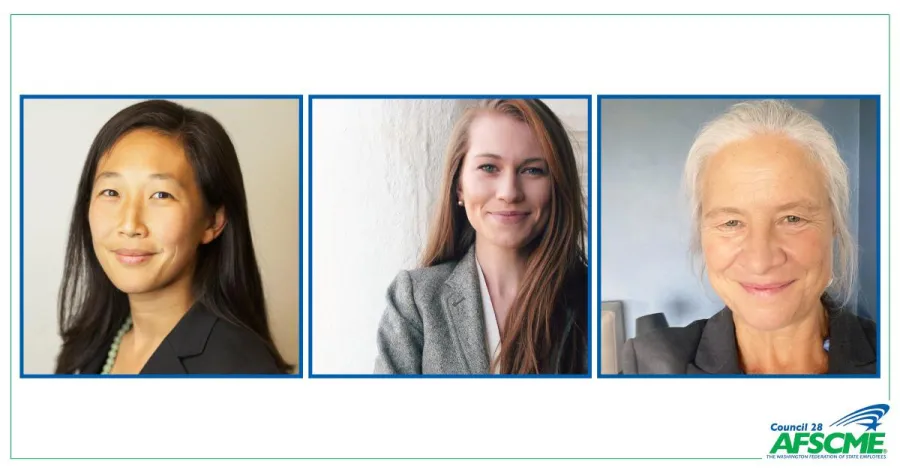

Representing the state were WFSE members and assistant attorneys general Marsha Chien, Andrea Brenneke, and Lane Polozola and Legal Assistant Caiti Hall. Hall is president of WFSE Local 795 and Brenneke is an executive board member of AWAAG-AFSCME Local 5297.

“Many people told us this case was unwinnable,” said Hall, who helped prepare over 900 exhibits used in the trial, presented those exhibits during witness examination, and ensured that technical difficulties didn’t interfere with the attorneys making their arguments.

“The state was definitely the scrappy underdog in this case. For the first virtual trial, our team essentially lived in a conference room in our Seattle office for a month before trial to make sure we knew how to use everything. For the second trial, which was in person, we studied the courtroom tech and practiced everything and came off very polished. The jury noticed, I think.”

“The lawsuit was successful because brave individuals were willing to stand up and speak out.”

What really made the difference in the trial was the detainees themselves. After a first trial ended in a hung jury in June 2021, the detainees nevertheless came back to tell their stories again in the retrial.

“I was worried they would get frustrated,” said Chien, who served as lead attorney on the case. “They faced cross-examinations that were difficult to sit through, questions like ‘Didn’t you get medical care?’ ‘Didn’t you get three meals a day?’ ‘You chose to come to this country, and now you’re asking for more money?’ But they came and they brought it. It meant a lot to me that they were heard.”

“Some of the witnesses had experienced extreme trauma in their countries of origin and made heroic journeys to the United States for safety and the freedom and opportunity our country promises,” Brenneke said. “It was heartbreaking to hear their stories, but it was also gratifying when our judicial system really provided an opportunity for them to speak their truth and obtain justice.”

Workers on the ground fighting back

Chien, Hall, and Brenneke see similarities between what they do as union members and how the detainees organized themselves.

“What put the Northwest Detention Center on our radar in the first place was detainee work stoppages,” Chien said. “These were effectively strikes that became rallying cries for the detainees and for community activists outside. The more organized the detainees were, the more they were paid and the better their voices were heard.”

“The lawsuit was successful because brave individuals were willing to stand up and speak out,” said Hall. “I was really inspired by all the witnesses. When we as a union see something wrong, we speak up. Otherwise nothing changes.”

Brenneke added, “The collective action and voice of the workers was necessary. No single worker could take on a NYSE corporation like GEO and prevail, especially as this litigation spanned four years and many original witnesses were deported and unavailable for trial when it finally happened.”

In October, the jury found that GEO Group had violated the minimum wage statute.

As a result, GEO owed over 10,000 former detainees $17.3 million in back pay. In November, the Court ruled that GEO owed an additional $5.9 million in unjust enrichment.

Hall recalls the jury coming back into the courtroom looking very proud. “It felt good to watch a group of Washingtonians say, ‘This is wrong, and you can’t do this anymore.’”

“The fact that a jury decided the case made me feel even better,” Chien said. “People from the community, my community, agreed that we were not going out on a limb. The minimum wage statute is actually very simple and very elegant; people doing work have to be paid. Work is work. Rules are rules.”

The whole team including private co-counsel.

Enforcing Washington laws that protect working people

Legislators and businesses did not bestow the minimum wage law upon workers. Generations of workers demanded it along with other fundamental labor laws like the 8-hour day and weekends. And without the continued engagement of workers, those laws would not be enforced.

The same is true of our union contracts. Even the most skillfully crafted contract requires the watchful eye of union stewards to ensure it is being enforced in every worksite.

“I came to this job because I am passionate about these issues,” Hall said. “I want to ensure the rights of all Washingtonians are protected. That’s also why I’m active in our union. I want to make sure my coworkers and I work in the best workplace we can. I see it as doing the same work in different arenas.”

Before she worked for the state, Brenneke advocated for employees’ rights in the private sector. When she joined the Civil Rights Division at the attorney general’s office, she wanted to make sure she was involved in employee advocacy in her own workplace as well.

“There was an organizing effort and I joined it,” Brenneke said. “I wanted to walk the talk.”

Are you connected with your Member Action Team?

A Member Action Team, or MAT, is a tool to build union power on the ground in worksites. It can help you and your coworkers in contract negotiations, grievances, collective actions, and anywhere you rely on collective power. Learn more.

Not a WFSE member?

Join 47,000+ WFSE members in speaking up for our jobs, families and communities. Join here.