Turning Frustration into Action—and a Pay Boost

Child welfare workers in Washington came together for a major win this year: in addition to advocating for much-needed cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), WFSE members led the charge in securing 10% assignment pay for the majority of child welfare field operations staff at the Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF).

In this truly-member run campaign, the question was not “’What is the union doing for me?’ but ‘What are we working on accomplishing together?”

Turnover, Underfunding & Staffing Issues

Fed up with years of witnessing their work be hampered by turnover, underfunding, and resulting staffing issues, activists from WFSE Local 889 and the DCYF Policy Committee worked extensively to lay the groundwork that made this victory possible. Their secret weapon? The member action team (MAT)—a structure to help union members connect at the worksite, form strong relationships, and work toward positive change.

The DCYF MAT team, fondly known as “Team Awesome,” had laid the foundations for success over long months of organizing their coworkers with a successful group grievance and job actions in a difficult climate.

Grassroots Organizing

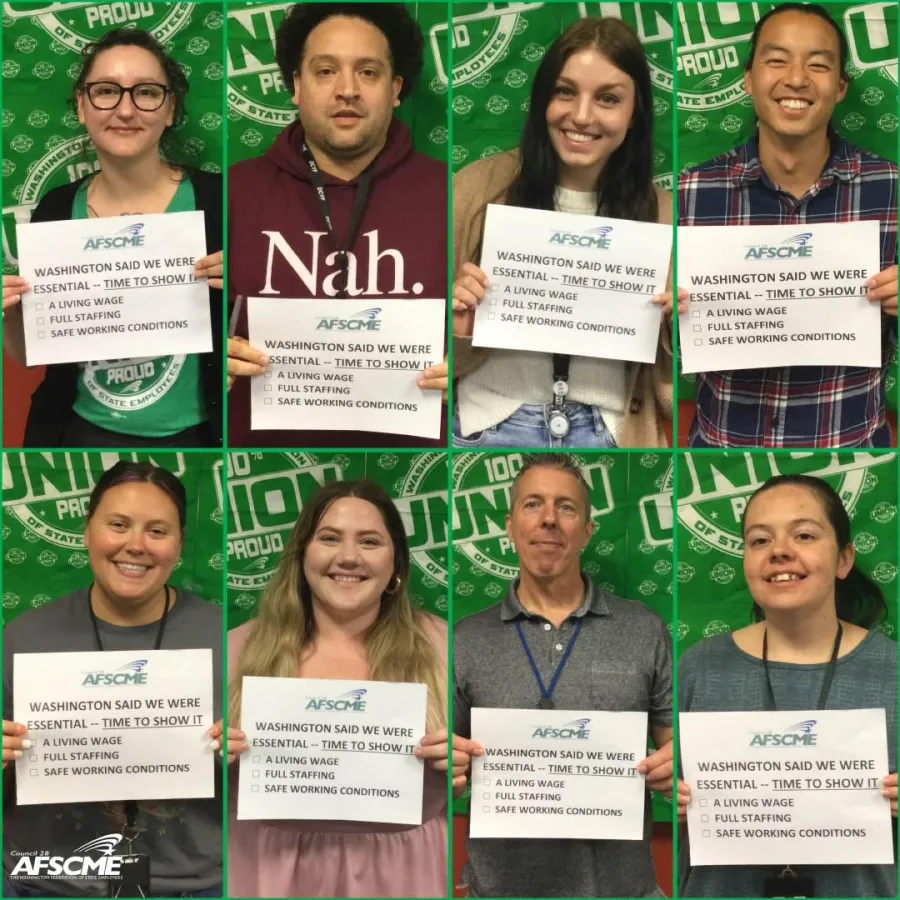

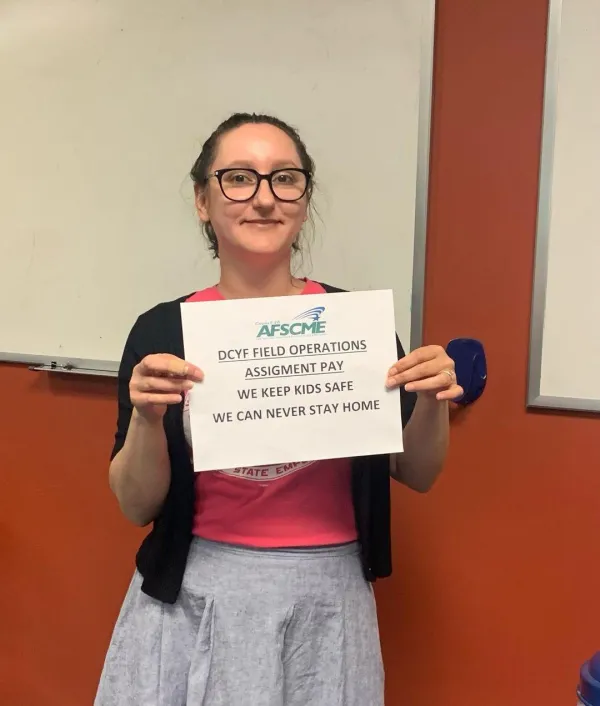

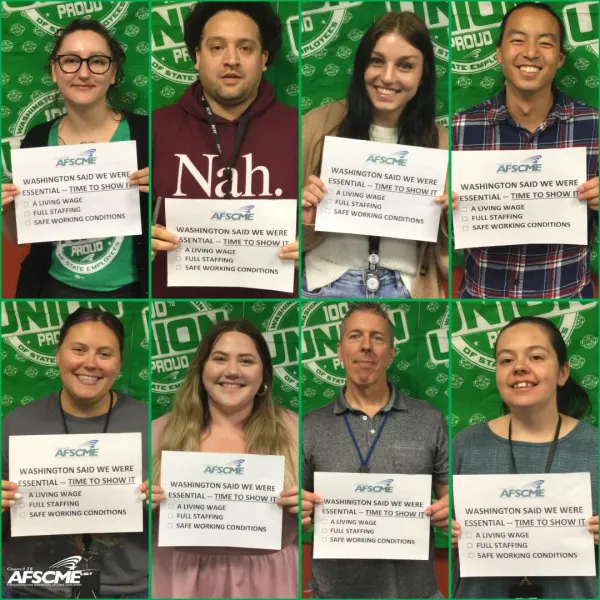

When contract negotiations began, DCYF activists were ready. Their massive grassroots campaign mobilized folks across the state with memes, social media, and in-person outreach, urging DCYF WFSE members to participate in photo campaigns, write letters and call Governor Inslee.

Jeannette Obelcz is the president of WFSE Local 889, a delegate to the DCYF Policy Committee, and a member of the WFSE Executive Board. She has worked at DCYF for seven years as a caseworker and supervisor. She currently supervises multiple programs, including family reconciliation services and family voluntary services.

[caption caption="Jeanette Obelcz" align="right"]

“It was a matter of laying the groundwork,” Obelcz said of winning the pay increases.

“When our team were in bargaining, we were doing a lot of education on social media and email blasts, talking about the importance of contacting the governor in regards to assignment pay and the COLA,” she said.

Turning Frustration into Action

The DCYF campaign offered frustrated child welfare workers the chance to address some of the pain they’d been experiencing during the pandemic and before—being asked to do more with less, bearing the brunt of public outcry over the dearth of foster homes, watching their dedicated and caring coworkers experience assaults and burnout at work—and the ever-present knowledge that soaring caseloads were preventing them from doing their jobs the way they were trained.

“We were giving people an outlet to express their frustration and advocate for themselves. We’re so short-staffed and have been for so long,” Obelcz said.

“We have workers who’ve spent countless late nights working with youths out of placement, trying to find placements for them, being assaulted. It has an impact not only on them, but on their families and their relationships.”

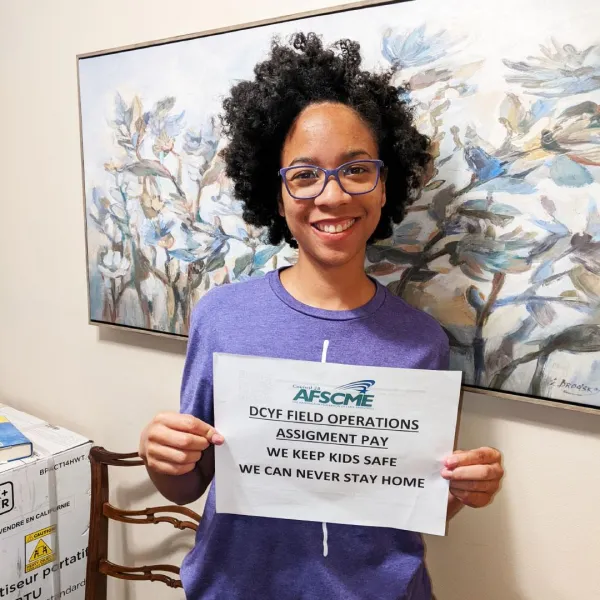

[caption caption="Riley Ingram-Sowell" align="left"]

Riley Ingram-Sowell is a social service specialist with DCYF, where she’s worked for five years. She’s passionate about improving outcomes for kids. For Ingram-Sowell, union activism is a way to stand in solidarity with her coworkers and actualize the hopes she has for kids and families in Washington.

“We are experiencing extensive turnover,” said Ingram-Sowell.

“It’s really hard to do the kind of social work we want to do when we are carrying nearly double the number of cases we should. The families we work with deserve more than just the minimum,” she said.

Keeping Families Together Amid a Staffing Crisis

Child welfare workers’ goals are always to prevent a child from needing to be taken into the care system when possible, to reunite families, and to minimize the time kids spend in the system. Across the country, child welfare advocates are increasingly calling for more resources to be allocated to services that help families resolve crises, such as the family voluntary services Obelcz helps to provide.

Child welfare workers at DCYF knew what would stem the tide of turnover and begin building toward a better work environment and better outcomes for kids and families: the caseworkers at the highest risk for assaults, contracting COVID-19, and other workplace issues needed a pay increase.

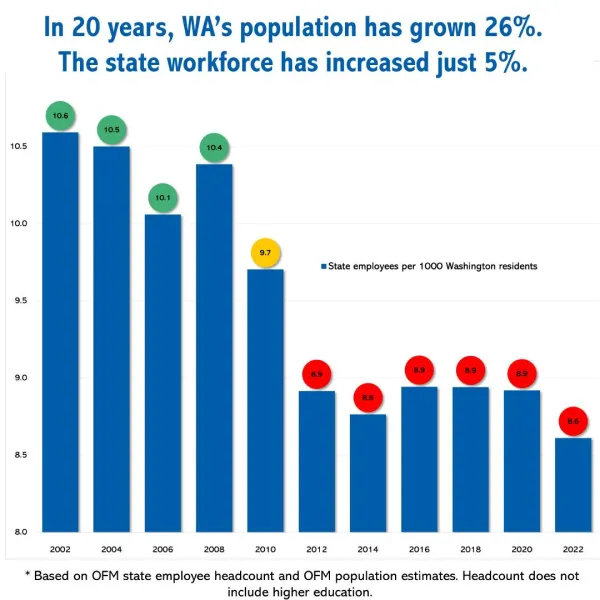

Fewer and fewer public workers are available to provide Washingtonians with the services they depend on. State government has yet to recover from the Great Recession. In 2002 there were just over 6 million residents with 63,975 general government employees serving them. In 2022, the population has ballooned to 7.4 million residents, but the state employee headcount has failed to keep pace, currently sitting at just 67,721.

[caption caption="Data from https://ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/budget/statebudget/18supp/highlights/budget17/11StateEmployees.pdf"]

Full Staffing Means Better Outcomes for Children

A fully-staffed DCYF with manageable caseloads is critical to both preventing trauma for kids and helping them to find stable placements if they do need to be taken into care.

“Every time a social worker leaves a case, it delays permanency for these kids for eight or more months,” said Ingram-Sowell.

“We don’t want kids to be in services for longer than necessary. Pay increases are key to get folks to stay in service longer and get the quality of service folks deserve,” she said.

Lack of Protection During Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic also brought new challenges to child welfare workers, particularly those who work in the field doing home visits, investigating allegations of abuse and neglect, and appearing in court.

“Those of us in child welfare never stopped going into the field,” said Obelcz.

“We were not provided with N95 masks, gowns, gloves, hand sanitizer, or wipes. All we had was cloth masks brought from home and strictly rationed Clorox wipes. We decided that we’d had enough,” she said.

Fighting at every level from offices, regions, locals, and statewide, the campaign cultivated new leaders across the state and provided as many opportunities as possible to connect with members. Leaders worked to identify gaps in participation and to listen deeply, connect with members, and reach out to new potential activists on several channels.

“As people who work in the social work field, we’re really good at advocating for families, but not for ourselves,” said Obelcz. “We were giving them a pathway to do that with this campaign.”

The Nuts and Bolts

Campaign leaders prioritized accessibility, holding DCYF Policy Committee meetings virtually to make it easier for people to attend, and used email blasts and social media to keep members updated during bargaining. They created talking points for workers to use in their advocacy, provided fliers, and remained dedicated to open and honest conversation about what was and wasn’t working during the campaign.

Throughout their efforts, DCYF activists focused on connection and education.

“It’s not ‘What is the union doing for me?’ but ‘What are we working on accomplishing together?” said Obelcz.

DCYF Attempts to Block Assignment Pay

Despite the urgent need, winning assignment pay at the bargaining table was an uphill battle. After months of participating in the photo and letter-writing campaigns, members were shocked to learn that their own agency had not supported the class-specific increases.

Instead of giving up, child welfare workers from across Washington upped the pressure on management to do the right thing. Letters poured in to DCYF leadership, and campaign leaders kept folks engaged with social media posts and emails.

“Everyone does really important jobs at DCYF, but when half of the DCYF workers who take cases are within their first year of employment, we need to retain that staff,” said Obelcz.

“Giving them that 10% for the additional liability they take on with the work they do in the courts is really important. It gives us a chance to retain some of our workforce.”

Solidarity, tenacity, and a deep commitment to helping kids and families had made the campaign a success.

Through grassroots activation of their coworkers and political advocacy up to the state level, WFSE members made their voices heard—and they’re not finished.

“Not everyone we wanted included got assignment pay,” said Obelcz. “Many other staff who also continued working in person in the pandemic, have unique court requirements, and face risk and secondary trauma at work weren’t included. We have continued to meet with management to advocate for those who were left out.”

“We want Washington to be a place where children grow up and have an incredible childhood and feel safe and loved and reach their full potential,” said Ingram-Sowell.

“This is an avenue to do that. We have to start by making sure we are funding services for our most vulnerable children,” she said.

Obelcz and Ingram-Sowell noted that the messaging for the campaign also emphasized solidarity with our union as a whole, drawing parallels between other public employees’ challenges in securing adequate funding for the critical services they provide.

“This contract isn’t just about DCYF, it’s all public services,” said Ingram-Sowell.

“We maintain our roads, we provide benefits to families in need. We keep Washington running!”

Want to connect with your coworkers and lay the groundwork for positive change at work? Considering starting your own member action team with our union.