Faced with Crises, WFSE Members Find New Value in the Union

Amidst a renewed movement for racial justice, a global pandemic, and a recession, workers across the country are seeing the benefit of unions more clearly than ever.

At WFSE, members are reframing racial justice as a “lunchbox issue,” arguing that it’s as central to the union’s mission as pay, benefits, or working conditions—that without racial justice, economic justice is impossible.

They are addressing life-threatening safety conditions and financial strain caused by the pandemic.

They are running for office to advocate for working families and supporting elected officials that will reject knee-jerk budget cuts and austerity measures à la the Great Recession.

Conversations with members from across Eastern Washington about these crises show a diversity of opinion on where WFSE can focus its resources to make the greatest impact.

“We need to start negotiating contracts with diversity in mind.”

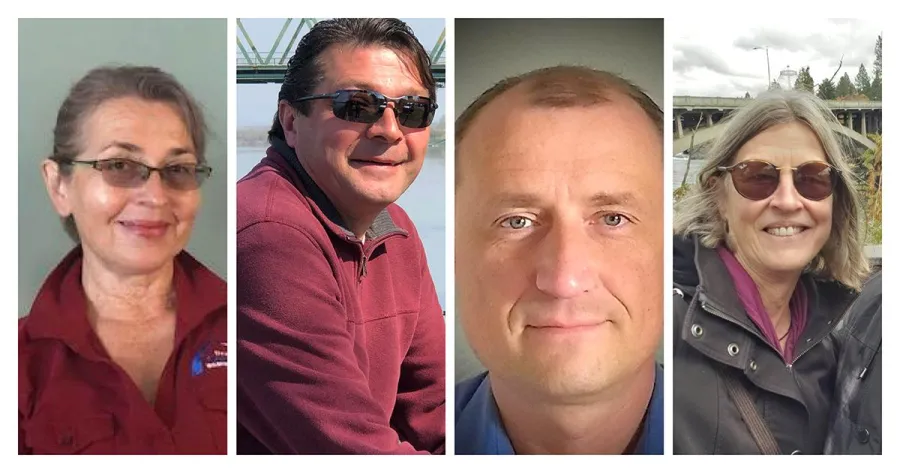

Elvira Farkas, who has worked in food service at Tri-Cities Work Release for a little over 20 years, is a shop steward for WFSE Local 1253.

Elvira works hard to educate her co-workers about their rights under the contract and to push for greater diversity and understanding at her worksite.

“I have seen lots of management changes and culture changes. Years ago, they tried to promote diversity. Officially they’re still doing it, but in the southeast region where I am, the committee doesn’t exist anymore.”

The Department of Corrections' own Equity Diversity, Inclusion & Respect Index stands at 57% (Not Satisfactory) and has dropped consistently since 2016.

Elvira thinks that for change to happen, people have to make it happen themselves, and pointed to the wave of protests following the murder of George Floyd as an example.

“People got fed up. You can only endure injustice for so long. It cannot last forever. We are seeing people getting killed in front of our eyes on TV. How much more proof do you need to see what is going on? It’s up to the community to rise up. This is how all movements started in the past. If you don’t take action, nothing is going to happen.”

Elvira is happy with the direction WFSE is moving in but thinks more work needs to be done.

“In order for us to reach real racial justice, the labor movement needs to start talking to people from a young age. We have D.A.R.E. programs with young kids to keep them away from drugs, but nothing to confront racism.”

Elvira also thinks diversity and racial justice need to be enshrined in contracts.

“We need to start negotiating contracts with diversity in mind. We need to push state agencies to hire more diverse people—perhaps even require that a percentage of new hires be Black, Hispanic, or women, for example. If you want diversity you have to be intentional. You have to push for it.”

“We are a melting pot in the country and in the union. You can’t say the union should just be about economics.”

The only person who has worked in food service at Tri-Cities Work Release longer than Elvira is her husband, Almir Mulasmajic, who was hired when the facility first opened in 1999.

“I came with the blueprints,” Almir likes to say.

Elvira, a Catholic, and Almir, a Muslim, escaped the ethnic and religious war in their native Yugoslavia thanks to a program for mixed marriages, arriving in Eastern Washington in 1997 with six bags.

Almir agrees with Elvira that the Department of Corrections needs to do more to promote diversity.

“I was a member of the Diversity Council for 10 years and was the diversity chairman for the Tri-Cities region. They still have the program on paper, but nothing happens. They follow guidelines regarding discrimination, but they don’t go beyond that. After 9/11 there was talk about protecting us Muslims from discrimination, but it ended there.”

Almir thinks WFSE and the labor movement should take a leading role in furthering racial justice.

“We are a melting pot in the country and in the union also. You can’t say the union should just be about economics. Changing hearts and minds is very hard. My suggestion is that the union tries to push education in the new contract, not just economics. For example, we have a diverse population of incarcerated individuals. Don’t you think we as workers would have a safer work environment if we had a diverse staff that matches the inmate population?”

Since becoming a shop steward in 2001, co-workers have gotten to know Almir as he’s helped them resolve grievances and hold management accountable for following the provisions in the contract.

Most recently, Almir was fighting vocally with management for not following health guidance.

“The health guidance came from the Department of Corrections, and then management would water it down, picking and choosing what to follow as they went. They did it on a case by case basis, which makes no sense.

"Three inmates were sent for testing after the agency received tips about positive cases at their job placements, but they were allowed to mingle with the rest of the inmates and go out shopping in the community before their results came back. One of them ended up testing positive.”

“The working class is being disproportionately taxed.”

Koastyantin Unguryan is a spoken language interpreter that has helped Russian-language speakers in and around Spokane access healthcare for the past 21 years. He came to the United States in 1995 from Ukraine.

His work, which has taken on new urgency during the pandemic, ensures that residents with limited English proficiency can access healthcare services, effectively communicate with doctors and nurses, and receive quality care.

As a member and district chair of Interpreters United, WFSE Local 1671, a statewide local of interpreters, Koastyantin keeps members informed of union business and gets activists involved in union causes.

Koastyantin feels that the most important thing WFSE can do right now is to ensure its people have jobs and can continue the working of the state. That means the wealthy will have to start paying their fair share.

State agencies have been asked to submit proposals to cut costs by 15 percent in response to the projected $9 billion revenue shortfall. Without action, a 25 percent cut across the board in all the departments where WFSE members work is possible.

“Preservation of jobs translates to the preservation of services for the people of Washington state, in particular, services for the most vulnerable in our society.

"In essence, the government is an instrument of the wealthy, and the working class is being disproportionately taxed. The easiest thing for politicians to do is to get their red pens and start making cuts. If you look up taxation in the United States in 1960, the top rate for single filers on income above $200,000 [the equivalent of $1.5 million today] was 91 percent.”

Today, at the federal level, that same person pays just 37 percent, but that figure is further reduced by tax loopholes.

“The very wealthy are able to circumvent taxation with tax advisors and tax lawyers who can shield them.”

Washington state has the most regressive tax code in the country. Those making less than $24k a year pay the greatest share of the little they have to support the infrastructure we all benefit from. Roughly 18 percent of their income goes to state and local taxes compared to just 3 percent for the super wealthy.

“I am very concerned that we do not create a rift between people pushing for structural change and law enforcement members.”

Llyn Doremus is a hydrogeologist who has worked on water quality regulation for over 30 years—in Africa, at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, at the Nooksack Indian Tribe, and for the last eight years at the Department of Ecology.

Her work ensures that Washington residents and the agricultural industry, which is so important in the eastern part of the state, get good, clean water that meets quality and health standards.

Llyn is highly involved in the union.

She supports her co-workers as a shop steward, serves as the chairperson for the Natural Resources Policy Committee, is a member of the Legislative and Political Action Committee, and sits on the Finance Committee of the Executive Board.

Like many members, Llyn recognizes the need for police reform.

“I’m sensitive to what people of color are experiencing in this country, and have experienced. It’s not a new thing by any means. I could go through and enumerate what could be done better in law enforcement. But right now that’s not my goal. I believe as a union member to make progress we need to be working together.”

She also recognizes that law enforcement and corrections officers have been put into impossible situations by the gutting of services, particularly mental health services.

“We all deal with cutbacks, but typically those cutbacks do not carry through to reductions in funding for law enforcement. Inadequate financing of social services means that those responsibilities end up getting dumped onto our law enforcement community, and they’re not in a position to be able to succeed. It is unfair.”

Llyn believes that for organized labor to meaningfully improve racial and economic justice for its members and society, it must be united.

“I am very concerned that we do not create a rift between people pushing for structural change and law enforcement members. This is not their fault. This is the fault of the structural inequities in this country that have been rampant for hundreds of years, and continue to be.”