Supreme Court decision in Janus threatens the quality of public-sector jobs and public services

Key data on the roles these workers fill and the pay gaps they face

Report • By Celine McNicholas and Heidi Shierholz • June 13, 2018

In the last decade, an increasingly energized campaign against workers’ rights has been waged across all levels of government—federal, state, and local. Much of the focus of this anti-worker campaign has been on public-sector workers, specifically state and local government workers. For example, several states have passed legislation restricting workers’ right to unionize and collectively bargain for better wages and benefits.1 Beyond these legislative attacks, public-sector workers have been targeted by repeated legal challenges to their unions’ ability to effectively represent them. The Supreme Court will soon issue a decision in the most recent of these challenges, Janus v. AFSCME Council 31. As a previous EPI report explained, the corporate interests backing the plaintiffs in Janus are seeking to weaken the bargaining power of unions by restricting the ability of public-sector unions to collect “fair share” (or “agency”) fees for the representation they provide.2 In this new report, we argue that the decision in Januswill have significant impacts on public-sector workers’ wages and job quality as well as on the critical public services these workers provide.

Fallout from legislative attacks on state and local government workers

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the plaintiffs in Janus, the decision will weaken the bargaining power of state and local government workers. Other attempts to weaken the bargaining power of public-sector workers and cut their pay have hurt public servants and the services they provide. These other attempts have often been framed as defending taxpayer interests—taxpayers who are supposedly forced to subsidize allegedly overpaid government workers. In reality, state and local government workers—who, as we later show, are if anything underpaid—provide services on which the vast majority of taxpayers depend. These workers are teachers, social workers, police officers, and firefighters. In fact, in dollars-and-cents terms, efforts to shrink state and local workforces and reduce public-sector workers’ compensation in order to reduce taxes disproportionately benefit the wealthiest households. Wisconsin provides an important example of this impact. Lawmakers there passed $2 billion worth of tax cuts in 2011–2014, paid for by the layoffs and wage and benefit cuts of public employees. Far from benefiting the average taxpayer, fully half of the tax cuts went to the richest 20 percent of the state’s population.3

Further, an examination of Wisconsin’s education system reveals negative outcomes following the passage of a law that virtually eliminated collective bargaining rights for most state and local government workers. Far from improving public services, after the law passed, teacher turnover accelerated and teacher experience shrank; nearly a quarter of the state’s teachers for the 2015–2016 school year had less than five years of experience, up from one in five (19.6 percent) in the 2010–2011 school year.4 These data demonstrate that attacks on state and local government workers are likely to result in reductions in the quality of public services on which most state residents depend. For families who depend on public education, maintaining a stable, experienced education workforce is critical. And it is the stability and experience of state and local government workers—and the quality of services they provide—that is at stake in the Supreme Court’s decision in Janus.

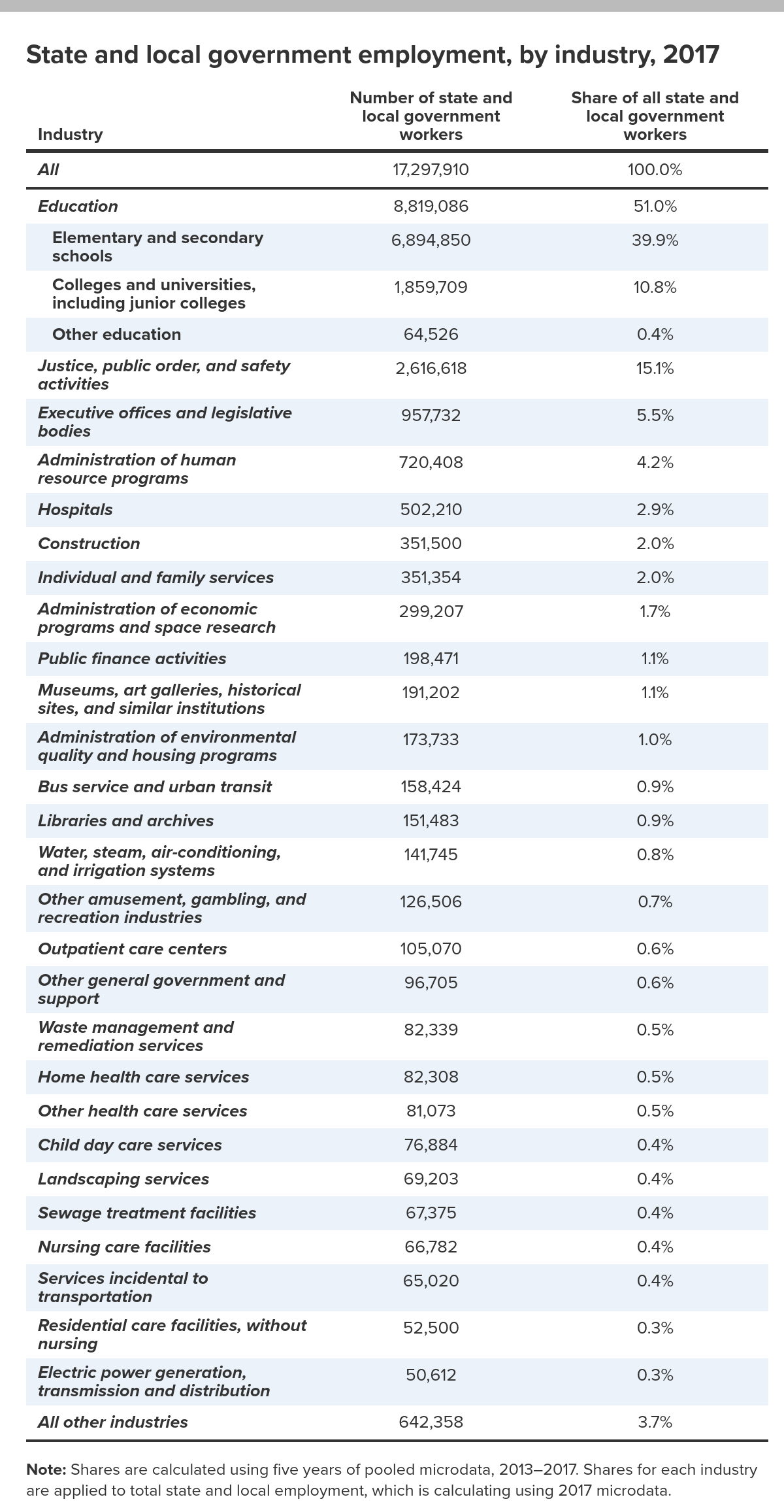

State and local government workers provide critical services

The effects of decimated collective bargaining rights on Wisconsin’s education system should be especially concerning given the sheer number of educators—over 8.8 million—employed in state and local government nationwide and thus potentially affected by Janus. The vast majority (6.9 million) of state and local workers employed in education are in elementary and secondary schools. Table 1 shows the industries that employ state and local government workers. Workers in education make up more than half (51.0 percent) of all state and local government workers, with elementary and secondary school workers alone making up nearly 40 percent (39.9 percent). In addition to education, millions of state and local workers work in justice, public order, and safety activities (primarily police officers and firefighters); hospitals; individual and family services; bus service and other urban transit services; museums and similar institutions; libraries; home health care services; waste management services; child day care services; and on and on. These are the critical public services that are put at risk when attacks on public-sector collective bargaining erode compensation and job quality for these workers.

State and local government workers provide important services while being relatively underpaid, not overpaid

As argued earlier, the claim that government workers are overpaid is a legislative ploy used to cut pay and curb bargaining rights. State and local government workers already earn less than similar private-sector workers. In particular, comparing the hourly wages of state and local government workers with those of private-sector workers, after controlling for education, age, gender, race, ethnicity, state, and other factors known to affect pay, we find that workers in state and local government make between 3.7 percent and 8.2 percent less on average than their private-sector counterparts.5 As shown in the next section, weakening public-sector unions will only exacerbate this public-sector “pay penalty.”

State and local government workers—like all workers—do better with collective bargaining rights

State and local government workers who are represented by a union earn substantially more than similar workers who are not. A careful analysis of wage data shows that state and local government workers who are covered by a union contract earn between 10.7 percent and 13.6 percent more in hourly wages than their nonunion counterparts with the same level of education, experience, etc.6 To provide a sense of the scope of this pay boost for union workers—and the corollary pay penalty for nonunion workers—consider a full-time, full-year state and local government worker who is in a union who earns roughly $40,000 a year. A similar state and local government worker who is not in a union would earn between $35,200 and $36,100 on average.7 That $4,000 or $5,000 less per year for the nonunion worker could, for example, be the difference between being able to save for a down payment on a house—or for a child’s college education or a secure retirement—and not.

The benefits of union representation are similar for women and men working in state and local government. Hourly wages of unionized women in state and local government jobs are between 9.7 percent and 12.7 percent higher on average than for nonunionized women in state and local government jobs, while the wages of unionized men in state and local government are between 9.2 percent and 12.1 percent higher on average than wages of nonunionized men in state and local government.

The benefits of union representation for state and local government workers are also very large for workers of color. Within the state and local government workforce, wages for black workers are between 10.4 percent and 12.4 percent higher on average than wages of nonunionized black workers. The wages for Hispanic and Asian workers in state and local government get a particularly large boost from union representation—by between 16.0 percent and 17.9 percent for Hispanic workers and between 16.6 percent and 17.8 percent for Asian workers.

These findings are consistent with other research showing that unionization confers wage benefits on workers in both the public and private sectors.8 In addition to wage benefits, union workers in general are more likely to be covered by employer-provided health insurance, and union employers contribute more to their employees’ health coverage than comparable nonunion employers. Workers in unions are also more likely to have paid sick days and paid vacation and holidays. Finally, union workers have an advantage in retirement security, both because union workers are more likely to have retirement benefits and because, when they do have retirement benefits, the benefits are better than those provided to comparable nonunion workers.9

Conclusion

Given the links between union representation, pay, and job quality summarized in this report, we argue that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Janus will likely have far-reaching implications for the nation’s 17.3 million state and local government workers.10 But this case goes beyond its impact on these workers. Critical public services stand to be affected as well.

The decision may lead to greater instability in state and local workforces, which would result in disruptions in the critical services these workers provide—services on which communities depend. The recent teachers’ strikes in states such as West Virginia and Arizona provide examples of the likely effect of denying workers effective collective bargaining.11 It is likely that other state and local government workers would be forced to resort to similar tactics following a Supreme Court decision in favor of the Janus plaintiffs. This means that more communities may face disruptions in the delivery of child and elder care services, public safety services, and municipal services.

This is what is at the core of Janus—whether a group of wealthy donors and corporations will be allowed to rewrite our nation’s rules to serve their own interests at the expense of the public good.12 The financial backers of this litigation likely do not rely on public services to educate their children, care for aging parents, or provide support for disabled family members. Increasingly, the wealthiest interests in this country are able to bypass the state for fundamental services. As a result, they exist apart from local communities and divorced from a shared interest in many public services. This results in cases such as Janus in which wealthy, corporate interests look for ways to reduce public spending on services that they don’t need to rely on. In Janus, these wealthy corporate interests are not just attacking state and local government unions’ ability to protect good, middle-class jobs in public employment—they are also attacking the crucial services on which most Americans depend.

Endnotes

1. Gordon Lafer, The Legislative Attack on American Wages and Labor Standards, 2011–2012, Economic Policy Institute, October 2013.

2. Celine McNicholas, Zane Mokhiber, and Marni von Wilpert, Janus and Fair Share Fees: The Organizations Financing the Attack on Unions’ Ability to Represent Workers, Economic Policy Institute, February 2018.

3. Gordon Lafer, Attacks on Public-Sector Workers Hurt Working People and Benefit the Wealthy, Economic Policy Institute, April 2017.

4. David Madland and Alex Rowell, Attacks on Public-Sector Unions Harm States: How Act 10 Has Affected Education in Wisconsin, Center for American Progress Action Fund, November 2017.

5. To estimate wage differences, we use ordinary least squares to estimate a wage equation using pooled Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group (CPS-ORG) data from 2013–2017, restricting the sample to wage and salary earners ages 18–64 who are either state/local government workers or private-sector workers. For the base specification, we regress log hourly wages on dummies for being a state/local government worker, level of education, race/ethnicity, foreign-born status, gender, and state of residence, along with age and age-squared. The values given are coefficients on the state/local government worker dummy; the range is the result of the inclusion or exclusion of industry and occupation dummies in the specification. Note that by using hourly wages in the regression, we have accounted for the fact that some workers—for example, teachers—often don’t work all year.

6. To estimate wage differences, we use ordinary least squares to estimate a wage equation using pooled CPS-ORG data from 2013–2017, restricting the sample to wage and salary earners ages 18–64 who are state/local government workers. For the base specification, we regress log hourly wages on dummies for being in a union, level of education, race/ethnicity, foreign-born status, gender, and state of residence, along with age and age squared. The values given are coefficients on the union dummy; the range is the result of the inclusion or exclusion of industry and occupation dummies in the specification. Note that by using hourly wages in the regression, we account for the fact that some workers—for example, teachers—often don’t work all year.

7. This range is calculated as $40,000/1.107 and $40,000/1.136 and rounded to the nearest $100.

8. Josh Bivens et al., How Today’s Unions Help Working People: Giving Workers the Power to Improve Their Jobs and Unrig the Economy, Economic Policy Institute, August 2017.

9. The benefit comparisons in this paragraph are for all workers; they are not specific to state and local government workers as in the wage discussion. For more information on the benefits of unionization in general, see Josh Bivens et al., How Today’s Unions Help Working People: Giving Workers the Power to Improve Their Jobs and Unrig the Economy, Economic Policy Institute, August 2017.

10. For data on the size of the affected workforce and other key facts, see Julia Wolfe and John Schmitt, A Profile of Union Workers in State and Local Government: Key Facts about the Sector for Followers of Janus v. AFSCME Council 31, Economic Policy Institute, June 2018.

11. West Virginia prohibits collective bargaining for state and local government workers, as reported in Natalie Delgadillo, “Do Weak Labor Laws Actually Spur More Teacher Strikes?” Governing, April 3, 2018. West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arizona are so-called “right-to-work” states with weak or no public-sector collective-bargaining laws, which has led educators to “press their demands through mass protest and the disruptions in public services that those entail,” notes Jason Walta in “Teachers Walkout without Bargaining Rights—Why It Matters for Janus,” ACS Blog (American Constitution Society), April 5, 2018.

12. Celine McNicholas, Zane Mokhiber, and Marni von Wilpert, Janus and Fair Share Fees: The Organizations Financing the Attack on Unions’ Ability to Represent Workers, Economic Policy Institute, February 2018.

See related work on Collective bargaining and right to organize | Public-sector workers| Unions and Labor Standards | Wages | Supreme Court | janus-v-afscme-council-31

See more work by Celine McNicholas and Heidi Shierholz